User stories are easy to create. Just think of a type of user– mother or student, and what they might want to accomplish. A mother may want to find coupons for her essentials and students may want to find places with discounts for them. Scenarios however dig a bit deeper. They provide the situation and underlying reasons that bring users to interact with a service.

Why scenarios > user stories

With background and context, it’s easier to think of optimal solutions to accomplish tasks instead of a generic one-size-fits-all approach. The goal is to attract a loyal user base that extols the virtues of our services, and not casual users that will bounce as soon as something more fitting comes along.

How many should I make?

But of course, just like with research and stories, we could have an endless list of scenarios. How do we know when to stop? Using the research.

Through the results from interviews, surveys, and other sources of user information, we are able to pinpoint their non-negotiable demands as well as their frustrations, their pain points and their gains. Using my affinity diagram, I was able to quickly check why existing solutions leave users frustrated and options they would like to see. I quickly drafted many user stories based on the personas’ pains.

Creating scenarios

With this information, I can create scenarios and propose solutions that address their woes. Also, scenarios can be aspirational. They may or may not provide a solution, and I may or may not have capacity to provide such a feature, but they certainly show why certain features should be invested in and developed.

Scenarios also outshine stories through their ability to help find solutions with a lower risk of misdiagnoses. Vague user stories leave designers scratching their heads but overly specific ones prime certain solutions to the detriment of other more optimal ones. But through interviews and contextual inquiries, UX researchers can discover the reason behind these pains and frustrations. This information can then be used to create a scenario to think of solutions to address the underlying issue. I juxtapose what they cannot do, or not well, with the reason they drives them to want to do so.

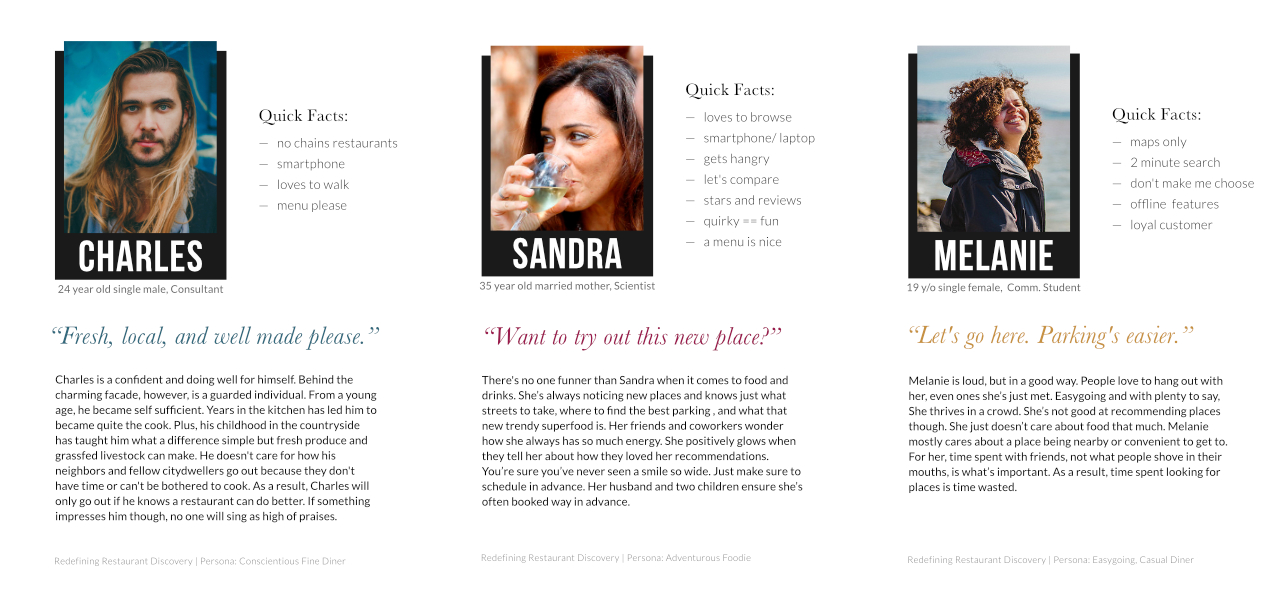

For example, one interviewee expressed interest in downloadable maps for offline use. She didn’t always have internet and wanted to quickly navigate through town. We could have left it as is: “As a easygoing diner, I want to have maps available offline”. But some probing revealed that what was actually desired was to know where certain amenities could be found, such as grocery stores, transit stations, public restrooms, and maybe bars. In other words, she wanted to be able to explore a town for her usual needs despite intermittent internet access.

Steps to create a scenario

- Choose your persona (click here to see the post explaining the personas I created)

- Look for pains in your affinity diagram or research findings

- Create lots of user stories for the persona based on the pains

- Select unusual stories as well as a few common stories

- Expand on these stories and provide reasons based on the persona.

- Make sure they aren’t generic. These reasons should not easily fit with another persona.

- Optional: Provide an open-ended solution (not designing yet) without mention of specific tools or interfaces (keep options open)

Examples galore

As I love examples, here are some more. Below are four scenarios created for Sandra based on her persona’s desires and behaviors.

…

Shall I go today or tomorrow?

(There are two for comparison purposes)

Sandra loves to look at menus and get a gist of the price and also selection. She doesn’t want to miss out on something because it’s only offered on Mondays and she goes another day. So she goes to pull up the menu. The app brings her to the photo gallery where several photos have been labeled as the menu, with the most recent listed large (and the others underneath with smaller thumbnails). She can swipe between different shots of the menu.

Sandra wants to know if the gas station is still open. She sees that her favorite one is closed, but another more far away is open. She wonders if this station is a rip off though, because of its proximity to the freeway. Sandra decides to check if someone has posted an image and lo and behold, under the prices section, she found a photo of prices posted yesterday. It’s almost 20 cents more per gallon than what she paid last week at her spot, so she decides to wait a day. The next morning, after getting gas at her spot, she takes a photo of the prices and posts it on the application for others.

Where are the useful reviews?

Sandra has learned to be wary about online reviews. So many comments harp on what are inconsequential details for her. Instead, she sees what her nearby trusted friends have tried and are recommending. She notices a review posted by a nearby user whose review she has already liked and clicks again that it’s helpful. This helpful reviewer gets a notification, adds her as a friend, and messages her to say hi and talk about this new place she loved.

I have some time to kill.

Sandra has just finished lunch early and has two hours to kill before her friends arrive. She decides to see what’s nearby, especially as she had received a notification about being near one of her marked spots to try. Pulling up the map, she notices four different places, two places to try, one favorite, and a 5 star rated. Instead of going to her usual hang out, she decides to check out one of the new places. Looking at the photos, she chooses the quirkier one.

…

Next Step:

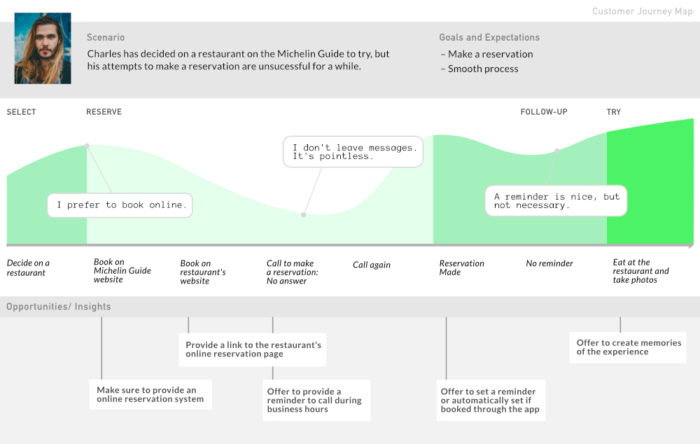

– Selecting several scenarios to draft up some customer journey maps

Note: I personally like to provide solutions, which are italicized.. But I always focus on the background story more and am open to iterating on them to better serve the users.

Did I miss anything about scenarios? I’m still learning so please share your thoughts in the comments below.